The idea of “being Chinese” has become, for some, a vital yet fraught issue.1 For most, “being Chinese” has not been a contentious matter, as it has been accepted unthinkingly as simply aligned with a taken-for-granted sense of nationality and identity. In recent decades, though, along with the emergence of activist contestation of identity politics across the globe, academics have more extensively scrutinized questions of identity. Whether geopolitically, ethnically, and/or culturally defined, a certain sense of “being Chinese” has been promoted by the prc’s regimes during the course of the last century. Since the 1990s, there has been a substantial increase in scholarship that critiques the imposition of a singular definition or way of “being Chinese” and its consequent implications. In this respect, we highlight Tu Weiming’s “Cultural China” (1991), Allen Chun’s Forget Chineseness (2017), and Gregory Lee’s book China Imagined: From European Fantasy to Spectacular Power (2018).2

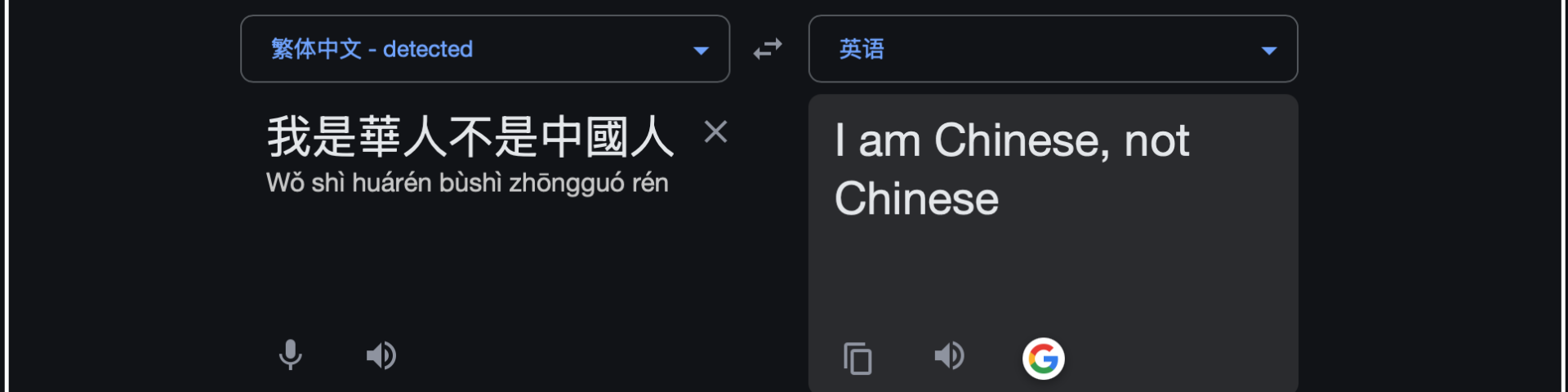

An illustration of the complexity of Chineseness arises from a meme derived from the quirk of the phrase “我是華人不是中國人” (Woshi Huaren bushi Zhongguoren) becoming “I am Chinese, not Chinese” when translated in Google. The meme, which had gone viral, exposes a problem implicit in English vocabulary which lacks additional English words for translating two different Chinese terms and concepts. The meme dwells on the apparent confusion of the Google translation: “I am Chinese, not Chinese.”

Using this meme as a point of departure, Shih Fang-long has conceptualized and curated this special issue to address the arising question of “What’s in the Name Chinese?”, with the aim to clarify what is implied by the English term “Chinese” and the nuances of disambiguating it. Throughout the special issue, we employ the concept of sous rature (“under erasure”) by crossing out the first English word “Chinese” (used in translation for 華人) while keeping its legibility in place: “Chinese.” This approach combines the strategy of erasing while simultaneously acknowledging the trace.

1 Outline of the Special Issue

The question of Chineseness/Chineseness has been extensively discussed among the authors through a series of lse working seminars which, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, initially took place virtually. This special issue features three articles that raise a diversity of issues, such as migration and settlement patterns, colonial and postcolonial dynamics, political legitimacy, cross-Strait relations, and identity politics. It synthesizes perspectives from multiple disciplines including anthropology, architecture, history, international relations, political science, sociolinguistics, and urban studies. These articles were presented at the 2022 Annual Conference of the lse Taiwan Research Programme and the 2023 Annual Conferences of the American Association for Chinese Studies, and benefited from constructive feedback from panelists and discussants, significantly enhancing their quality.

Our special issue investigates and reassesses the cultural, economic, linguistic, political, and social facets of Chineseness and Chinese identity within a broader context—both in China and across East Asia, emphasizing border-crossing networks and their manifestations and contestations. It aligns closely with the objectives of the Journal Translocal Chinese: East Asian Perspectives, which is distinguished by its commitment to an in-depth study of overseas Chinese communities, embracing their variety and complexity. Specifically, both our special issue and the journal Translocal Chinese have critically rethought “the local” and have advanced innovative “translocal” perspectives and approaches in the transnational and comparative study of Chinese overseas.

This article serves as introduction to the special issue. It attempts to offer a theoretical prelude laying the foundation for the critical positioning and interpretative framework employed in the examination of particular historical and empirical cases discussed in the accompanying three articles. Our approach provides a dynamic and critical exploration of the concepts 華人 (Huaren) and 中國人 (Zhongguoren), enhancing the understanding of these terms by situating them within broader contexts in comparative perspective. Our objective is to contribute meaningfully to the interdisciplinary discourses surrounding these terms and identities, enriching the conversation on China, Chinese, and Chineseness.

This special issue notes a bifurcation with regards to the connotations of 華人 (Huaren), revealing a nuanced division that mirrors complexities over time (as discussed in Liang Chia-yu’s article) and space (as explored in Izac Tsai’s and Doreen Bernath’s article), and the hyperspace of internet platforms (analyzed in Shih Fang-long’s article). In the internet hyperspace, Shih argues and demonstrates that within the prc Great Firewall, the “officially correct terminology” is: 華人也是 [is also] 中國人, which co-implicates the two terms, endowing them with a singular, fixed, and primordialist sense. Beyond the Great Firewall outside the prc, there are suggestions that 華人不是 [is not] 中國人, implying that the two terms are separable, with 華人 as a hybrid, hyphenated, and localized notion, indicative of some changing senses of identity played off against 中國人.

In article one, Liang Chia-yu, expert in Chinese politics and international relations, offers a profound implication associated with the terms 華性/中國性/Chineseness within the framework of his interpretation of Chinese International Relations Theory (Chinese irt). Liang re-examines three pivotal concepts—Tianxia (天下, All-under-Heaven), Dayitong (大一統, Grand-Unity), and Zhengtong (正統, Authentic-Unity)—which he contends collectively form the bedrock of imperial China’s legitimacy. The traditional definition of Tianxia lays the ground for prc scholars to designate “the integration of all lands, all hearts, and all peoples on Earth in a world institution.” Specifically, Liang asserts that the notion of “Authentic-Unity” encapsulates a legitimate political order, signifying a spatial unity authorized by its historical predecessor and temporally succeeding the prior unity. This authentic succession, according to Liang, became politically imperative following the establishment of the Grand-Unity (since Emperor Qin) effectively normalizing territorial unity as a paramount determinant of legitimacy. Liang further contends that over time the prc’s monopolization of Chineseness—and the reproduction of that monopoly in its Chinese irt—constitutes a cornerstone for the legitimacy of the prc’s regime operating through the ccp. Liang’s article validates Shih’s finding that 華性/中國性/Chineseness are co-essentialized such that they are imbued with a singular, fixed, and primordialist interpretation within the prc Great Firewall.

In article two, K.B. Izac Tsai and Doreen Bernath, from the perspectives of migration and spatial movements in architecture and urban histories and theories, seek to reconnect discourses on the urbanity of Southeast Asia with the region’s long history of maritime trade and migrating societies. In terms of space and identity, they delve into the dynamics between Huaren—a particular category of people with their transoceanic network connecting distinct ports of Southeast Asia—and Huabu, a portal-spatial pattern of trading, settling, and moving of Huaren communities. Through exploring the origins and connections of the terms, “Huaren” and “Huabu,” as entities distinct from “Chinese” and “Chinatown,” they present evidence and fresh insights into transnational and trans-territorial urban systems. Thereby, they broaden the interpretation of 華 (Hua). They unveil alternative perceptions of 華 evident in a Southeast Asian urban history, characterized not by power centers or a unified ethnic and identity perspective but by a perspective which focuses on “vessels” and on what happened on the margins. This perspective links with the fluidity and interconnectivity of sea-bound endurance, commercial dynamics, ritualistic diversity, and cosmopolitan values. Tsai’s and Bernath’s article corroborates Shih’s observation that 華人/Chinese, increasingly divergent from 中國人/Chinese, can represent a hybrid, multifaceted, and localized concept, reflective of evolving nuances of identity.

In article three, Shih Fang-long, a specialist in the anthropology of Chinese societies, analyzes a meme that presents itself as a machine-generated translation imitative of Google. She explores the evolving bifurcation in the usage, meaning, and connotations of 華人 “Huaren.” This reveals a divergence in interpretation of 華人/Chinese—contrasting bushi (is not) with yeshi (is also) 中國人/Chinese. This split mirrors a division between social media platforms located outside the prcGreat Firewall and those within it. Shih highlights the prc’s stance as fixing the two terms as equivalent. Beyond the purview of the prc, however, she suggests that there seems to be an emerging and changing range of what the terms connote. In response to the plurality and fluidity in how the term Huaren is deployed, Shih suggests, in a radical lexical maneuver, that it might be retranslated by her newly coined umbrella term, “Huabrid.” By this neologism she seeks to capture elusive senses of Chinese, and to describe the complexity of ethnic/cultural identities that have arisen since people of Chinese connections emigrated to Southeast Asia, Taiwan, and beyond. Now for some the term represents a potential rupturing from the prc-defined and -imposed sense of a singular ethnic/cultural/national identity. Furthermore, Shih utilizes Bernath’s concept of “re-constituted locality” to navigate the discourse on “the local,” which avoids both what Bernath terms “the euphoric global” and “reductive localism” (see the next section). Reconstituting locality entails both mobility of subject and subject areas, alongside the construction of an alternative “locality of thought” and “location of culture.” Bernath advocates for “translocal” perspectives and approaches that define the local as inherently relational, specific, partial, and plural, thereby countering the dual pressures of globalization and localization (see the next section). Shih concludes that employing two separate English terms, “Chinese” and “Huabrid,” enables a more precise representation of the various senses of “the local,” Chineseness, and the identities they (could) signify.

The authors of this special issue have reached a consensus on the implications of “What’s in the name ‘Chinese’.” They would like to limit usage of the English word “Chinese” to specifically denote associations with Zhongguo, or more precisely, the People’s Republic of China. Conversely, they use the Romanization of 華 (Hua) to indicate non-Zhongguo contexts and concepts. In his article, Liang Chia-yu critiques the prc’s fixed interpretation of “Chinese” and its primordialist connotation of “Chineseness” in a manner that co-essentializes and thereby ambiguates the distinctions between 華 (Hua) and 中國 (Zhongguo). Izac Tsai and Doreen Bernath originally Romanized 華 as “Hwa,” reflecting the common spelling in historical and missionary writings about the Chinese settlers in Southeast Asia during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. However, they have since reverted to “Hua” as a more contemporary usage, correlating with Huaren and Huabu. Whether transcribed as “Hua” or “Hwa,” the term highlights the fluidity and interconnectivity of sea-bound endurance, commercial dynamics, ritualistic diversity, and cosmopolitan values. Shih Fang-long’s suggestion of the novel term “Huabrid,” playing as it does on the term “hybrid,” is her bid to better describe foreign passport holders with Chinese connections. By leveraging the “hybrid” nature of the word 華, Shih aims to transcend traditional assumptions about origins, permanent contexts, and predefined concepts. Instead, she wants to emphasize a fostering of changing identities which have adapted to specific contexts and localities of confluence and transition.

The authors have made concerted efforts to name concepts and contexts previously unnamed in English, leading to instructive divergences. Tsai and Bernath introduce “Huabu” while Shih coins “Huabrid,” neither of which aims to replace or be confrontational with traditional nomenclature such as that associated with “Chinatown,” “Chinese sojourners,” or “Chinese overseas.” Instead, “Huabu,” along with the newly proposed “Huabrid” and “Hua-logy,” enrich and re-orient the discourse, highlighting the plurality that exists both within and beyond the conventional boundaries of “Chinese” and “Chineseness” in terms of name, approach, and practice. This realignment of terms suggests an alternative logic of locality becoming reconstituted in contemporary usage. Doreen Bernath elaborates on “Hua-logy” and its “translocal” implications in the next section.

2 Translocation and Hua-logy

As the euphoric embrace of the global wanes at the turn of the twenty-first century, there is a defiant return of the local, yet driven by polarizing imperatives. On the one hand, there is the local in identity politics that competes in the arena of nationhood and cultural representation, as a kind of localism championing homogeneity, integration, and settled security; on the other hand, a different kind of local has been sought, intending to transcend the geographically-bound formulation of the local anchored to place and as a centripetal point of reference of identity, culture, history, and tradition. In order to go beyond the location-centric framework, there has been growing interest and impetus to develop so-called “translocal” perspectives and approaches, which have been characterized by emphases on fluidity, connectivity, plurality, hybridity, and heterogeneity.

In his critique of the “location of culture,” Homi Bhabha quotes Renée Green’s reflection on cultural differences, which he had characterized as “a kind of fluidity, a movement back and forth, not making a claim to any specific or essential way of being.”3 This is followed by the recognition of both projective and retrospective processes, constituting a “hither and thither” transitioning. But extending beyond Green’s architectural analogy of a stairwell as an epitome of liminal space, Bhabha’s suggestion is that transitioning should be understood as a “vessel.” This vessel is not that which sails “beyond,” as Bhabha warns, but that which needs to re-enter the conundrum, the blind spots, the denied presence of now. In this sense, the vessel of transitioning is understood as both projective and introjective, being instrumental in constructions of both identity and counter-identity, i.e. the “other,” in connection to locality, as well as indicative or illustrative of how estrangement and displacement alter and pluralize the assumed self. This analogy of the “vessel” becomes the theoretical hinge to the understanding of “Hua” and its transitioning “-logy”. And the term “vessel” is employed in Tsai and Bernath’s article to provide a vital way of exploring the settlement conditions of dispersal and confluence of Huaren migrants and their migrating space, following transoceanic settlements and manifestation of urban spatiality in colonial Southeast Asia.

When subjects transition, locality becomes decentralized and deterritorialized, which in turn may be defined through the relation of multiple places, the confluence and co-existence of different groups, a conception of identity through encounters and displacements, and transformation of communities and environments as shared experiences. Thus, it is no longer adequate to be “local” by articulating narratives of rooted tradition and situated knowledge. Being “local” cannot, then, be reduced to association with a singular place or people born out of the logic of history. Instead, in recognition of the acceleration of experiences of networked relationships and transferences from the material to the informational, the demand for recognition of those uprooted or becoming diasporic, the reclaiming of the deprived voice and place of those subjugated, and the acknowledgment of trans-territorial collectivity, “trans-locality” enables the articulation of “local” as intrinsically relational, specific, partial, and multiple, resisting the twofold forces of globalization and localization.

In Mark Cousins’ lecture titled “The Locality of Thought” that offers a critique of the false opposition between rationalism and relativism, he reveals that they both correspond to a profound movement of Western metaphysics, which is the attempt to think—in a way that negates location—about things called “thoughts” and about things called “objects;” but, he argues, these things have locations.4 He explains, “The emergence of the distinction between thought and object is also the distinction, as it emerges, between no-place and place. “Therefore, he continues, this is, unavoidably, the reason why” the human sciences are always condemned to say two things at once. Things that have a place and things that don’t.” Cousins has identified such a tendency, the paradigm shift in the epistemological structure of human sciences, to attempt to think in general about things in their specificity, as symptomatic of modernity’s inevitable desire to claim and impose universality by elevating one localized observation or representation over others, and likewise, to claim specificity despite maintaining a detached view. Any arising “general” case, thus, is consequential of an enlarged local case, where the intricacies specific to its location are necessarily abstracted and enlarged as pervasive to qualify the enquiry as delocalized “thoughts.” At the same time, these generalized thoughts are projected and objectified to re-present the locality back to itself, producing “objects” that are meant to represent the specificity of the location, but with new “names.”

Such has been the case with “Chinese studies,” subsumed within the profound movement of Western metaphysics and caught in what Cousins described as the perceived need to have and not have a location. While specificity is assumed to be shared across a variety of locations with “names”—Zhongguo, Zhonghua, Hua, Huaxia, Han, Tangren, Chin/Qin, or Sin/Sinae/Sino—the differences embodied in these locations of different names, and thus, the locations of different thoughts, have become increasingly less distinct. The “-logy” that defines the subject of study of Zhongguoyanjiu/Chinese Studies/Hanxue/Sinology has long afforded distinctions in terms of perspective and content; however, these productive distinctions have recently begun to blur and assimilate. This projection towards universality, the legitimacy to think without location, has been further instrumentalized by the politics of national identity and cultural hegemony, reducing the plurality presented by these names. The relation between locality and knowledge has been further reduced by the integrated nomination of “Chinese studies,” which in turn acts as a filter to arrest how one thinks, regards and interprets location-specific objects of knowledge, narratives, discourses and material evidence. This is an increasingly exacerbating practical problem faced by scholars working—from both within and outside of the Far Eastern and Southeastern Asian contexts—to develop diverse and critical reinterpretations on historical and sociocultural phenomena in and around these related regions and communities.

Another problem arising from the process of introjective recognition is the persistent Occident-Orient dichotomy intrinsic to much Euro-American discourse. Such discourse is inclined to seek a counterpart that can be rationalized under its epistemological framework of empires, civilizations, and dominant cultural centers, thus complicit in the conflation of a generalized “Chinese” category that sits comfortably with, and even reinforces, the power dialectics. To re-establish variants in name and in location, and to persist in working with non-interchangeable specificities and differences in objects and thoughts, as this special issue attempts, is precisely to resist such instrumentalization and to disperse the dialectical axial of centric views. For instance, what may constitute the logic of space, faith, movement, and trade relations in research described and adumbrated as “Hua studies” or “Huarenyanjiu” should not be subsidiary to, nor readily assimilated with, any of the above-named studies. Rather it should maintain a sense of being distinct yet without being exclusive. This is the potentiality of displacement, not replacement.

Bernard Faure suggests, as a sinologist unraveling the condition of “immediacy” in Zen Buddhism, that traditions do, consciously or not, give voice to the other. The condition of multivocality can never be fully repressed by the controlling projection of univocality, the ideal of the orthodox. Faure makes reference to James Boon’s argument that, although normalized from within, traditions “nevertheless flirt with their own “alterities,” gain critical self-distance, formulate complex (rather than simply reactionary) perspectives on others, confront (even admire) what they themselves are not.”5 In this sense, Hua-logy appears as such “alterity” in the dominant field of Chinese-logy, where the seemingly stable and integrated sense of traditions both resists and seeks desired anomalies as triggers of possible transformation. These could be manifested in aspects of socio-spatial occupations and religious rituals, which follows the twofold logic according to Jeanne Favret-Saada, where logical and pre-logical thinking co-exist not as two irreconcilable realms but as linguistic and thought positions that can be occupied in turn at various times. The presence of multiple yet specific locations of thought drives the necessity of differentiated structures of nomination and signification. The maintenance of discrepancy observed by Faure, or the interstitial arising through the displacement of the domains of difference argued by Bhabha, point to the process that “takes you ‘beyond’ yourself in order to return, in a spirit of revision and reconstruction, to the political conditions of the present,” to the possibility of multivocality.6

Taking a closer look at the history of “Sinology” reveals a pluralistic set of approaches that have addressed a subject of study with or without the imperatives of specifying a location. Leigh Jenco argues for the importance of both specifying and pluralizing the location of studies, rather than dipping into the impulse to construct a “third space,” i.e. the universal non-place, to stage dialogue or contrast. To do this we must reconceive the “local” not as a cultural context that permanently conditions our understanding and argumentative claims, but as a particularized site for the circulation of knowledge.7 She uses two examples from Asian experience in her research—indigenization movements in China and Taiwan, and the historical practice of Sinology by Japanese and Euro-American scholars—to demonstrate the analytic purchase of this recalibrated notion of locality. Both examples belie the widely held assumption that location-specific inquiry necessarily circumscribes subsequent attempts to pursue alternative perspectives or interpretation on foreign grounds. To re-open these inquiries that can go beyond self-reflexivity locked in location specificity, producing what may be called “de-centered theory,” it is important to reconceptualize “the more radical possibility of re-centering the constitutive terms, audiences, and methods of theoretical discourse.”8

Significant efforts have been made for countering the Global West by constructing alternative “area studies” frameworks, such as the Global South and the Global East in postcolonial discourses. The de-centering drive tends to seek a possible “replacement,” a legitimate substitution, where a different center, arisen at a different location, can be elevated to the level of the non-local, the universal. A different approach may be, instead, to reinscribe local particulars as sites of general knowledge-production, which in turn recognizes that local communities are actor-participants that possess their own alternative epistemological framework and frontiers of the unknown that can be the grounds of self-critique rather than be subsumed as prescribed elements in the existing field of knowledge.

Jenco reveals the indigenization tendency as a kind of “forced relevance,” an imposed “nativist cause,” that aligns the context and research, as well as the researcher(s), granting a representative assumption and a sense of urgency.9 An example of such indigenization as a tendency is the emergence of recent variants on Taiwan and ongoing critiques by Japanese of the conflation of Chinese thought with “Confucianism” (ruxue; in Japanese, jugaku), hinging on Chinese as a native anchor as opposed to what may be Euro-American thought. Regardless of their target of attack, these movements demand greater responsiveness to native conditions by local scholars on the basis of a presumed connection between scholarly research and its social, cultural, or historical context. Jenco uses another example to disclose how Sinology in Japan before the Meiji era (1868–1912) “blurs the line between its object and method of research,’ to the extent that it can be described as “translocal.” Sinology in Japan during that time can be described as “the study of Song and Ming dynasty neo-Confucianism with no recognized distinction between these Chinese philosophical imports and Japan’s own schools of thought,” it was accepted in the Japanese education system to counterbalance the dominating influence of Western philosophy.

Another effort to pluralize sinological frameworks can be learnt from Tamara Ho, who argues for a “feminist sinological method” that can attend to critical modes of intersectional studies on “situated and embodied contestations of identity categories (e.g., ‘Chinese’ or ‘minority’) as well as border-crossing currents of imperialist, nationalist, and neoliberal traffic and exchange.”10 Ho grounds her approach on examples of what she calls “counter-hegemonic formation,”’ referencing, for instance, work by Shih Shu-mei, Tsai Chien-hsin and Brian Bernards, that “deconstructs Han-centered and nation-based notions of Chineseness.”11 The meta-discourses of feminist sinology in Ho’s view closely reflects Shih’s proposition on Sinophone, i.e. a diasporic sinology, that resonates with our conception of a possible Hua-logic that rides on mobile and hybrid agencies to traverse and straddle normalized practices and cultural anomalies, i.e. the alterities that traditions persistently seek.12

This also brings into question the legitimacy of using categories from Western philosophy to describe traditional Chinese thought. From the point of view that relies on local specificity and native anchorage, recourse to key Western concepts for the interpretation of traditional Chinese thought would be perceived as heresy. However, from the point of view of a reconstituted center that Jenco argues, a hybrid of cultural ingredients and specific trans-positioning can be recognized and can trespass the discourse. In this sense, the relevance of traditional Chinese thinking to modern phenomena can only be understood if there are detours through other cultural domains and agencies, such as Confucianism (which requires a Sinological detour), and modern Chinese language (which itself requires a Japanese translation detour). For instance, Francois Jullien, contemporary to Faure, frames his study on “blandness,” a particular thought motif in his Sinology, by connecting scholarly heritages originally localized within Chinese elite discourse with particular sites of philosophical conceptualization in the Hellenic traditions. This resonates with Faure’s deliberate entanglement between particular conceptual and ritualistic tendencies in the Chinese Zen traditions with the psychoanalytical anthropology of Jeanne Favret-Saada and Pierre Bourdieu’s theory on practice contingent to local and personal experiences. The foreign-local dichotomy is resisted by recognizing and actively forming companionship across cultural, geographical, temporal and linguist boundaries in the discovery of new knowledge and relation.

Thus, reflecting on the consequences of these debates, redefining “locality” becomes necessary to the unraveling of alternative logics as active and contingent sites of being-able-to-think-together across recognized differences and detours. To avoid the kind of epistemic violence much too easily committed in both traditional and de-centered debates, the bond between culture and locality needs to move beyond the assumption of givens, origins, and permanent contexts so as to build relevancy through particular conditions of confluence and transition. This is where the reconstitution of a “Hua-logy” acutely revives the plurality of Zhonguoyanjiu, Huaxue and Sinology, and how the thinking through of one requires the detour in and out of another; all of these journeys and subject-bodies demonstrate the possibility of a mobile locality, of being “translocal.”

Going back to Cousins’ “locality of thought” and Bhabha’s “locations of culture,” the reminder here is of the specific yet plural signification of location, and the need to be aware and take account of not only what is particular in the objects of inquiries but also the mode of thinking through relations and “localization” that emerges in the process of engagement. “Hua-logic,” unfolded in the articles gathered in this special issue, exemplifies precisely that possibility to alter conception of localities even when addressing the same place; vice versa, locality is a matter of active reconstitution that involves moving and connecting between a plurality of places and identities. Translocation is as such a twofold empowerment of a locality that is not a priori to, but realized through, the recognition of the threshold of similarities and differences. Hence, “Hua Studies” is not constituted as a replacement of or to take over the domain of that which is converging as Chinese Studies. It functions as an alternative that opens up other possibilities of thinking and being together, and marking differences without becoming oppositional, i.e. an alternative logic of belonging and constituting locality. This is how Hua supplements and affords the productive divergences and plurality that is both within and across the thresholds of Chinese, in name and in practice.

1 We would like to express our deep gratitude to the American Association for Chinese Studies for their encouraging support and funding granted by their Special Project Committee for this special issue.

2 Tu Weiming, “Cultural China: The Periphery as the Center,” Daedalus 120, no. 2 (1991): 1–32; Allen Chun, Forget Chineseness: On the Geopolitics of Cultural Identification (New York: suny, 2017); Gregory Lee, China Imaged: From European Fantasy to Spectacular Power (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

3 Homi K. Bhabha, “Introduction: Locations of Culture,” in The Location of Culture (London and New York: Routledge, 1994), 2–3.

4 Mark Cousins, “The Locality of Thought,” presented as part of the conference “Relativism,” organized by the aa Graduate School / History and Theory Programme, Architectural Association School of Architecture, London, May 14, 1987, aa Archive, aa/02/02/09/01/03, accessed March 3, 2024, https://www.aaschool.ac.uk/markcousins/03.

5 Bernard Faure, “Epilogue,” in The Rhetoric of Immediacy: A Cultural Critique of Chan/Zen Buddhism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991), 309.

6Bhabha, The Location of Culture, 1.

7Leigh K. Jenco, “Re-centering Political Theory: The Promise of Mobile Locality,” Cultural Critique 79 (Fall 2011): 28.

8 Jenco, “Re-centering Political Theory,” 28.

9 Jenco, “Re-centering Political Theory,” 36.

10 Tamara C. Ho, “Border Crossing: Feminist Sinologies through a Southeast Asian Lens,” Signs40, no. 3 (Spring 2015): 698.

11 Shih Shu-mei, Tsai Chien-hsin, and Brian Bernards, ed., Sinophone Studies: A Critical Reader(New York: Columbia University Press, 2013); Shih, Tsai, and Bernards, ed., Sinophone Studies.

12 Shih Shu-mei defines Sinophone as “a network of places of cultural production outside China and on the margins of China and Chineseness, where a historical process of heterogenizing and localizing of continental Chinese culture has been taking place for several centuries.” Shih Shu-mei, Visuality and Identity: Sinophone Articulations across the Pacific(Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 4.